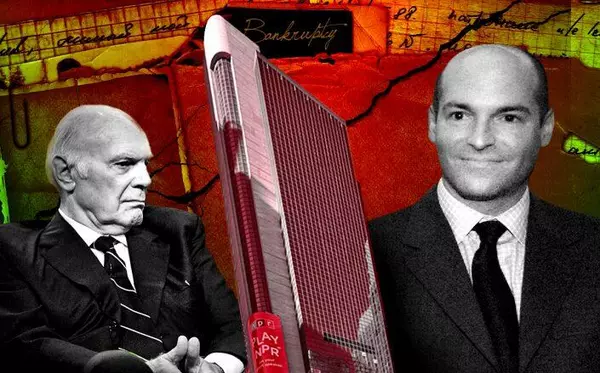

Checkout time: Aby Rosen booted from Gramercy Park Hotel

Aby Rosen has officially overstayed his welcome at the storied Gramercy Park Hotel. Rosen was ejected this week from his lease controlling the hotel by the judge presiding over a lawsuit filed by his landlord, the Goldman family’s Solil Management. The 190-room hotel, which featured Danny Meyer’s Italian restaurant Maialino and works by such artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst, shuttered its doors as the start of the pandemic in March 2020 and never reopened. Solil sued in April last year seeking damages of nearly $80 million and to oust Rosen from the property at 2 Lexington Avenue, which has been stripped of furniture and artwork and left to collect building violations. “We believe the property is not being maintained and is deteriorating,” Janice Goldberg, an attorney for Solil at Herrick, Feinstein, said during a hearing last week. Goldberg said Solil’s attempts to replace Rosen have been hindered because he won’t give the firm access to show the hotel to potential tenants. “Right now we cannot say to prospective tenants when we have any realistic expectation of being able to deliver the premises if we were to be able to enter into a new lease,” she added. A spokesperson for RFR, Roxanne Donovan, said, “Due to the impact of Covid and the terms of the lease, the tenant found it was no longer economically feasible to operate the hotel.” While the judge ordered RFR off the property, the matter of damages is still left to be decided. Rosen’s RFR Holding acquired the hotel with longtime friend hotelier Ian Schrager in 2003 and took full ownership in 2010. The ground lease on the property runs through 2078. Solil Management had sued to collect nearly $80 million in rent, but the judge in the case ruled that Rosen wasn’t personally liable for the sum. Solil has split their request for damages, laying out the $11.8 million figure and asking for additional “liquidated” damages that are yet to be calculated. Rosen’s attorneys neither disputed that his company owed rent nor opposed the order of eviction. But they argued that a collective bargaining agreement governing the hotel prohibited him from voluntarily surrendering it. The Gramercy isn’t the only trophy property that Rosen has had to give up. In 2020 he handed over control of the Lever House to Tod Waterman’s Waterman Interests and Brookfield after he got mired in a ground-lease dispute with his landlord at the property, the Korein family. Those troubles haven’t sidelined Rosen, though. He recently closed on a $290 million purchase of the office building at 475 Fifth Avenue in Midtown.

The consensus builder

From tackling the $2 billion Alameda Corridor project to bringing the Staples Center to life, Steve Soboroff has spent the last five decades bridging the gap between the city of Los Angeles and real estate developers. His latest undertaking — a rent relief campaign for police officers — is no exception. When we spoke in mid-May, he was in full dad mode, driving down from L.A. to Indian Wells with his son, Miles, who’s getting married there. “Tell him congratulations, then we can talk,” Soboroff said over Zoom, pointing his phone to Miles. He then proceeded to riff with The Real Deal about his real estate career, his run for City Hall and why he thinks developers are “boring.” What was your first real estate venture? At the University of Arizona, on my first day in 1966, they moved me into a dorm that had no air conditioning. They moved me in with a roommate and he kicked a hole through my closet door the first day. So I subleased my room. I had to get the hell out of there. Did you make a profit? [Laughs] No. You studied real estate as an undergraduate? A bunch of well-known, national real estate figures had retired to Tucson and were teaching. One of my teachers was the head of Federated Department Stores, which was Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, and another was Roy Drachman, who founded the Urban Land Institute and [was] the president of the International Council of Shopping Centers. I signed up for [these classes] knowing the struggle my parents were going through just for me to go to college. My folks had a retail store. They were working seven days a week, knowing that their rent clause in their lease was 5 percent [of sales] to the landlord. All he had to do was open his mail slot to get his money. My dad and my uncle knew this guy who became a shopping center developer who moved to Los Angeles and was successful, so I asked them if I could meet with him. Who was the guy? Joseph Eichenbaum. He was partners with Ben Weingart and they developed Lakewood Shopping Center. This was in 1969 and I asked him what classes to take in school. I didn’t know he only went to third grade. But, he told me what to take and I took all of them. I went back to him after I graduated and he told me to go get a Masters. It was extremely competitive. They said I had to take an admissions test. I scored in the 11th percentile. So they rejected me. But I went to the dean. I said, “I’m not going to enroll because I can’t get in, but I’m going to go anyway.” I think I alarmed him. I was the first civic activist in Arizona, I guess. So they let me in and I got the job. Eichenbaum offered me $750 a month. You’re probably saying, “Steve’s old. $750 a month — that’s not bad.” It was shit then. I could have gone back and said I needed more money. Or I could take his money and just make myself so valuable to this guy that he’ll have to pay me more and more. I was going to ask if you were satisfied with that. I could have gone back and said I needed more money, because that’s insulting. Or I could take his money and just make myself so valuable to this guy that he’ll have to pay me more and more. And that’s how I chose to work. Contrary to today, where people say “I’ll work, but I’ll work three days a week and I want to work remote from home.” I wanted to work seven days. It was a great experience. In 1978, I left there to start my own place. How’d you kick things off? I would contact retailers that weren’t in L.A., like Target, Office Depot. I said, “I’ll be your real estate department in L.A. I won’t charge you for anything. But every time I make a deal for you, I want you to pay me double what you would have paid [someone else]. I’m taking the risk on it, but I want the reward.” And they went for it. We had one year where we did 400 stores — and there were only three of us. In those days, I was able to save more than I spent. I bought a piece of property on Montana Avenue in Santa Monica. I opened an office there, and I kept doing leasing but started just buying little pieces of property, keeping out of the hair of the big boys. I didn’t have the confidence to compete, but I was very confident in my own niche. I had to get to know some people in L.A. So I started a class at UCLA in 1975 and I would invite 30 to 40 retailers to set up a booth in a hotel. It took off, 1,500 people showed up and it went on for 25 years. I stopped in 2000, because I was running for mayor. And being a developer and running for mayor were not synonymous in those days. Why do you say that? Because the D-word, “developer,” doesn’t sound like it has any public policy or any social ramifications to it. What made you decide to run? When our eldest son Jacob was born in 1983, we lived in [Pacific] Palisades and we took him to a park. There was a climbing structure, and I climbed up and I cracked the shit out of my head. I went into the Parks office and asked if they had a first aid kit. They opened these lockers and it was all first aid. They said, “We call the paramedics once a week.” I said, “Well why don’t you fix the equipment?” They said they didn’t have the budget; it’d take 11 years. So I called the city and went around and collected some money from people in the neighborhood. And we [fixed it]. [Richard] Dick Riordan was the Parks Commissioner at the time. A few years later, he ran for mayor. I remember, I was in my boxer shorts to pick up the newspaper and I went back inside and my phone was ringing. He said, “It’s Dick Riordan. Are you the guy who built that playground in 78 days when it was going to take me 11 years?” I said yes. He said, “Well I need you to help me turn L.A. around. I want you to go on the Harbor Commission. There’s a project that’s been stalled there for 23 years called the Alameda Corridor. It’s a way to get goods out of the port and double the capacity of the port. And I need you to put that together.” And I did. I met [billionaire] Phil Anschutz and in six months we put the Alameda Corridor together. It was a $2 billion project. It was simple. The deal that they were working on had no rent. In other words, they would decide how much rent to pay after it was working. You can’t do that in real estate. Then Riordan said to me, “You want to be on the Parks Commission? Go do it.” So I did. We built 123 parks in 24 months and we didn’t hire one person. After that, Riordan said, “You gotta run for mayor, man.” [At the same time,] one of the things he sent me was the financial statement of the Convention Center. They were losing money every year. So this is how the Staples Center — now the Crypto.com Arena — got started. How much was it losing? About $50 million a year — and they had just finished building it. You know, who would come out here to go to a convention, when they could go to San Diego or Disneyland? There was nothing around. So Anschutz had just bought the L.A. Kings and they were going to build a new arena in Inglewood with the Lakers. So I went to them and asked why not put it by the Convention Center? They said the city’s impossible to work with. I said, “If you pay for the building, I think we can get you the land. But don’t ask the city for things like government subsidies.” Why didn’t the City Council want it? They said it’s for the classes, not the masses. The cost of going to a Lakers or a Kings game is beyond my constituents, they said. So I went to the Clippers and [owner] Donald Sterling. They were playing at the [Los Angeles Memorial] Sports Arena. Sterling said he didn’t want to do it and said he was moving to Anaheim. Anschutz didn’t want the Clippers, but the City Council did [because the games were cheaper]. I went back to Sterling, and said, “I know you don’t wanna move to Anaheim.” And he goes, “Well, why do you say that?” I said, “Because you have got hives all over your neck and people like you don’t make decisions when they’re nervous. The best thing for you to do is go to the Staples Center.” And they did for three years and we got the deal. It was so broadening for me, the people I was meeting in every corner of L.A. were so different from the people I’ve been hanging around with — the white elites. I always thought I was sort of like a man of the people, but I wasn’t. I didn’t know how to celebrate diversity. So the reason I ran for mayor was: How could I not? My daughter Molly came up with my slogan: Vote for Steve or leave. The whole thing was so real and so fun. Were you still running your real estate business at the time? I was. But the people in my office were complaining. They said, “You’re never here.” And I said, “Well, you can complain that I’m never there, or you can tell the people we’re working with that we’re getting everything done. Tell them, he’s got access, he’s meeting people and he’s not just hanging around a bunch of real estate people.” So they basically did the heavy lifting, but I was there for the important things. I did both. I had to. There’s so much joy in the business and you guys are so smart. It makes me sad that you’re spending so much time being so one-dimensional. You lost the election in 2001. Then you took on Playa Vista. What was it at the time? It’s a part of L.A., but it was a big piece of land, about 1,100 acres. It was [owned by] Howard Hughes Aircraft Company. I went to the owners — the third owners who were now upside down $700 million on it — and they were interviewing for [someone to be] president. It was Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Oaktree Investments and some labor unions. I didn’t want to do real estate. Real estate was getting boring to me because it’s so one-dimensional. I spent all this time in public policy and all real estate seems to me — these guys sit around and talk about what is the internal rate of return, what is return on investment. I said, “What if I took this on as a public policy project to make L.A. a better place?” I wanted three times what the other guys were asking. I was coming off eight years of public service and not making any money. So my goals were, make traffic work, be a great neighbor, build housing for all kinds of people and create the greatest privately built park system in America and protect the environment. First I said, let’s hire felons to do the construction. Second thing was affordable housing. Then, we went from controversial to cool. We took all the wetlands and gave them away, sold them to the state. And that’s how Playa Vista got done. As I speak to real estate developers, the first thing I say is “I think you guys are boring. I love you, but you’re boring.” And they laugh. You know, who has got the nerve to say that to them. I said, “You don’t understand how important public policy is and not just making stuff for the 1 percent or the half of the 1 percent. There’s so much joy in the business and you guys are so smart. It makes me sad that you’re spending so much time being so one-dimensional.” Playa Vista is now known for being part of the tech hub of Silicon Beach. Do you give yourself credit for that? Well, that wasn’t my doing. We thought it would take years. I guess I helped get Electronic Arts there, which brought a lot of the gaming industry to Los Angeles. I worked with Elon Musk, because I wanted him to put the SpaceX headquarters there, but that didn’t work out. But along came Silicon Beach and Wayne Ratkovich [of The Ratkovich Company] and Lincoln Property Company – they did phenomenal work. You’ve been on the Police Commission for nine years and you’re spearheading the LAPD’s new rent relief program. How much have you raised through the Police Foundation? So the idea was to do two things, help a cop rent or rent to a cop. Donate to the police foundation and they’ll pay the difference — up to $1,500 a month. So what we have now, we have some units available to recruits that are $3,000 a month, where the landlords have lowered the rent by a portion. And we have raised over $800,000 in three weeks to pay the difference. And it’s just starting because we’re getting great landlords from all over the city and they’re saying they’re willing to reduce our rent. But I’ve only got a relatively finite time left before I’m termed out. I want to get this done. You recently endorsed Karen Bass for Mayor. I know all the candidates and I respect them all. The top five have done a lot of L.A. and I respect them all. I endorsed Karen because she has the ability to work with the system. She has the benefit of having contacts in Washington and in Sacramento, where all the money comes from. She has a better ability than anyone else to get those funds. It’s the absolute right time for her. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Oakland retail follows hard-hit segments on recovery trail

Oakland’s retail sector is making gains for the first time in four years thanks to a recovery for some of its hardest-hit segments, according to a new report by Marcus & Millichap. The general rebound traces its roots to the lifting of pandemic-related restrictions about a year ago, the brokerage’s second-quarter report found. “The recent employment growth in Oakland has been strongest within the leisure and hospitality segment, with restaurants and gyms being some of the most active space fillers of late,” according to the brokerage. The Oakland metro area, which takes in most of the East Bay, is trending toward first year-to-year vacancy drop for retail properties since well before the pandemic. “Vacancy in Oakland is set to record its first annual decline since 2018, reaching 5.5 percent by the end of this year,” according to the report. Vacancies remain above pre-pandemic levels but nonetheless offer a sigh of relief to retail landlords. Oakland’s retail landscape saw vacancies rise sharply and rents dip steadily amid the lockdowns and other restrictions of the past two years. Asking rates fell by around 2.5 percent each of the last two years but are expected to see a 9.1 percent hike this year. That would outpace expected increases in most of the rest of the Bay Area, and put Oakland’s average asking rate at about $31 per square foot annually. Areas of the Oakland market south of the city’s downtown––including upper-scale areas such as Alameda Island and San Leandro and Fremont––are the strongest in the East Bay in terms of vacancy rates, at 3.8 percent entering April. The north and inland areas of the metro market also made strong showings, ringing the city proper with gains. The vacancy rate in the inland submarket of Dublin-Pleasanton-Livermore fell nearly a full percentage point, the largest year-to-year decline in the metro market. “The metrowide pace of rent growth is largely carried by exceptional advances in the 80 Corridor and 680 Corridor South submarkets, where asking rents advanced over 20 percent last year,” according to the report. Single-tenant performance is strongest along the coast, while multi-tenant properties farther inland have been most successful in adding and retaining tenants. The recent conditions appear to have stirred the market for investors. The number of single-tenant properties that changed hands during the 12-month period ended in March matched the pre-pandemic level of 2019. “While entry costs are growing, sales pricing remains significantly below San Jose and San Francisco, suggesting more investors looking to establish a retail footprint in the Bay Area will acquire assets in Oakland,” according to the report. The market appears poised to continue its tightening, with less than 200,000 square feet of retail space in the pipeline as of April. That compares with a typical mark of 400,000 square feet before the pandemic.

Categories

Recent Posts